Landscape{s}

30 x 50 inches/ 76.2 x 127 cm, Handmade papier-mache tiles, Acrylic paint and UV Matte Varnish, 2023

The floral detail on the left is taken from a detail of a Jataka relief on the Bharhut Stupa now in the Indian Museum in Kolkata. Kashmir became an important centre of Buddhism during the rule of Ashoka (304 – 232 BCE). The 4th Buddhist Council was held there in 72 AD under the patronage of Kushan king Kanishka. Its traces have, however, all but disappeared from the region.

The bark of a tree painted within the composite geometric form is located in Amsterdam, where I live and work. The large floating disc filled in with decorative motifs by craftsmen functions as a moon, stitching these seemingly disparate landscapes together. These shapes are gleaned from the traditional Khatambandhi patterned ceilings ubiquitous in Kashmiri architecture.

The understanding of landscapes as grounds, or soils, which provide nutrition to my understand of art, and life, is gleaned through conversations with the Palestinian educationist Munir Fasheh.

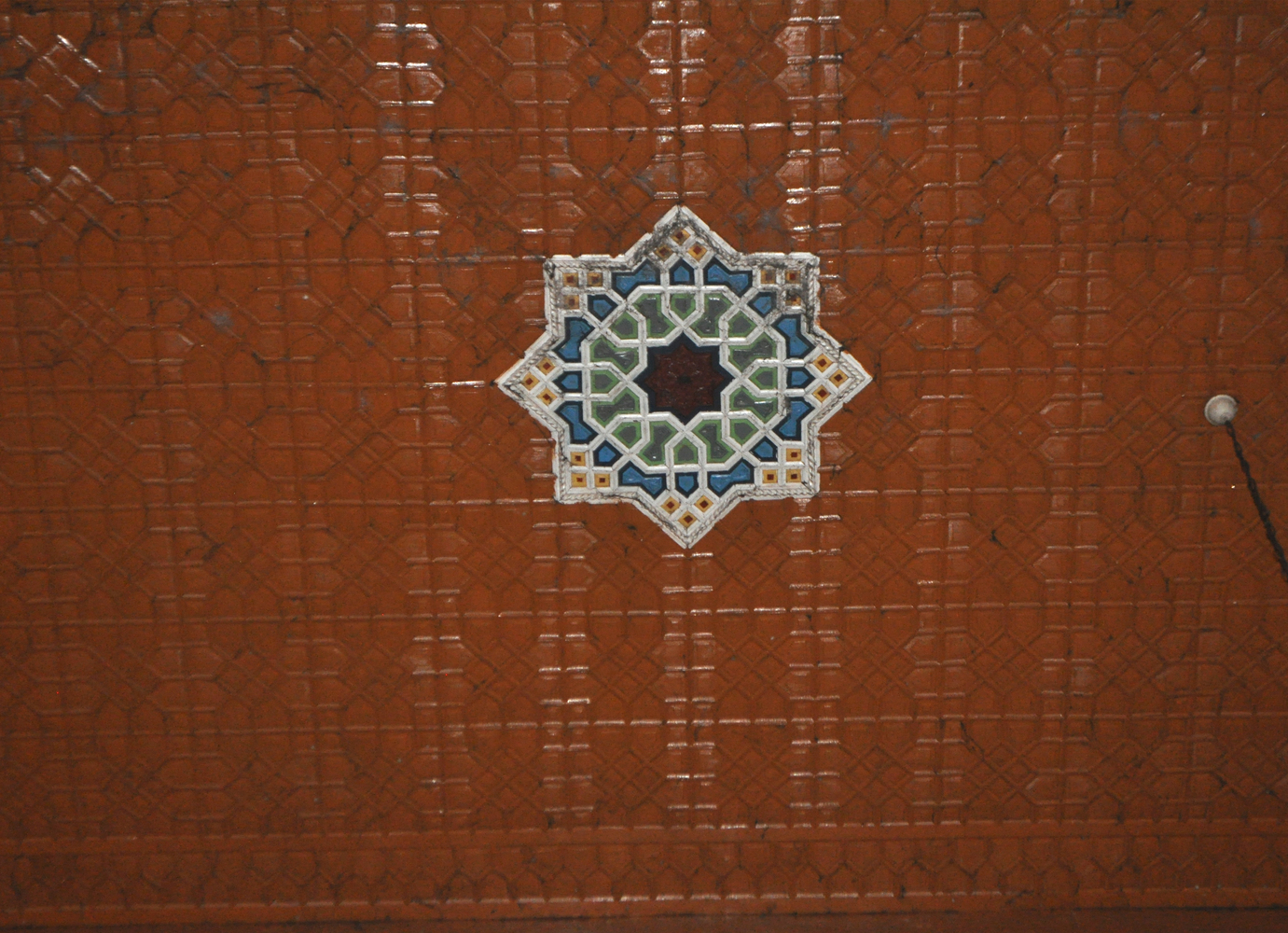

Above: Shapes that have begun to enter my work are collected from the architectural details of structures that I come across. This typical Kashmir wooden grill, or jaali, that I chanced across while visiting the Sufi shrine Ziyarat Naqshband Sahab in Srinagar, many years ago, led me to isolate the pattern, forming a geometric shape that I have often used within paintings ever since.

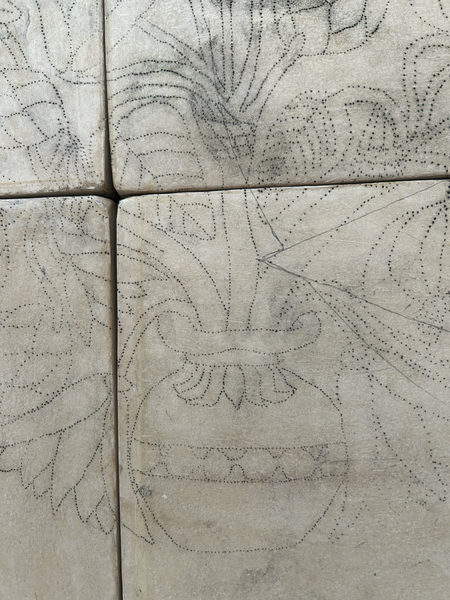

Below: A tracing of this Jataka detail from the Bharhut Stupa was made into a 'pounced diagram' so as to allow its transfer to the papier-mache tile, before being painted with golden decorative motifs by the craftsmen in Hasan Abad, in Srinagar. This is the traditional methodology by which patterns are transferred to the surface of papier-mache objects before being filled in by motifs and patterns typical to the region.

In Srinagar, I met a craftsman who excels in the art of Khatambandh ceilings. His tiny workshop, in his home, is filled with patterns cut out of local fir. Years before, his elder brother put together a manual of the patterns as a catalogue, and these contain the names of the patterns, probably passed down over generations. This particular pattern, which I utilised within Landscape{s}, amongst other works, is named Hasht Kabootar. Hasht in Persian means 8 sided, and Kabootar dove, or pigeon. This title points to the motifs Persian origins. And by naming it after a dove the author recognised the avian element in its shape.

It is filled in with the bark of an Oak tree I pass on my route to work in Amsterdam. The use of rough brushstroke against the delicate motifs filled in by craftsmen allows for the generation of texture within the composition.

Below: Khatambandh is the craft of geometrically patterned wooden ceilings that is typical to Kashmir. Below is a khatambandh ceiling from the Sufi shrine Khanqah-e-Moula, in Srinagar.

Over the years of working with craftsmen in Srinagar I found ways to subtly entangle myself within their methodologies, allowing for experimentation and translations within the work we create. I sit with them in the Karkhana, or workshop, and we make decisions together. The motifs they paint come naturally to them: It is an embodied knowledge, the skill that they carry within their hands, passed down from generation to generation.

This particular papier-mâché casket to the right was painted in by Ali, one of the craftsmen that works in the Karkhana of the master craftsman Fayaz Jan, with whom I have been working in Hasan Abad since 2014. His detailed craftsmanship is distinctive. The grey disc in the work Landscape{s} is also filled in by Ali.