I joined the University of California at San Diego in 1999. The graduate seminars on film were helmed by Jean-Pierre Gorin. One night, not long after my joining UCSD, Jean-Pierre walked into my studio and said to me, "the only interest in travelling is to lose ones luggage".

Gorin, sensing a world order was changing, would oftentimes barge into my studio with a copy of the Los Angeles Times, or the New York Times carrying an photograph that had caught his attention. They were images coming in from crises in the Middle East or South Asia. Gorin pointed out to me how much these images were connected to painting and thus linked to a culture of image-production.

An image that reflects these conversations well was taken by the French photographer, Alexandra Boulat (1962-2007) of an Afghan family burying their dead child at Maslakh refugee camp in Afghanistan in February 2001. Jean-Pierre came across this image in Time Magazine. He was struck by the the fact that image, of an Afghan family gently laying a dead child on a white shroud, immediately brought to mind the trope of the Pieta. It was thought such conversation that I became sensitised to the notion of framing, a subject that continues to within our dialogues and propels my work today.

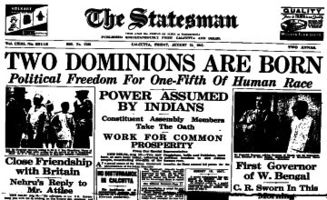

Gorin encouraged me to introduce these images into my paintings, a challenge. In Maine, when on a residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, in the summer of 2001, I began working on a composition based on the pieta image Gorin introduced me to. I returned to San Diego early September and a few days later, on September the 11th, the world turned over. Gorin collected me and a colleague, Kenny Strickland, early that morning and we drove across to a friend in Miramar, where together we watched on television events unfolding in New York. It was difficult to grasp: we had first to come to terms with the fact what we were watching was being broadcast live. People leaping from high, smouldering buildings, huge buildings crumbling and disintegrating, the cause of which were aeroplanes used as missiles.

I began collecting such images and those from the subsequent geopolitical narrative that folded, with the invasion of Afghanistan. The divide between imagery from occident and the orient could not have been more pronounced. If the image reportage from the Twin Towers and related events in the US were akin to an action movie, the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan unleashed a stream of images portraying a biblical landscape and people.

An interesting essay in Chapter 1 of Susan Sontag's “Regarding the Pain of Others” underlines this while poring over a triptych by photographer Tyler Hicks that appeared in the New York Times (November 13th, 2001, pg18) of Northern Alliance Soldiers executing a wounded Taliban soldier.

In 2002 I moved from California to the Netherlands to attend the Rijkakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam. Here the papers such as the Volskrant, Trouw and NRC ran photographs that were exceptional and my collection of images grew.

In Europe I was closer to India than in California and began travelling between the two continents again. It was 2002. The invasion of Aghanistan was in full swing, followed by the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Having left the United States at the end of 2001 at a moment the country was experiencing huge waves of resentment against immigrants, I expected in Europe a more nuanced political discourse. Immigration was a hot subject and being Indian, South Asian and whilst not at all religious, I found myself being sucked into arguments that were current at the time.

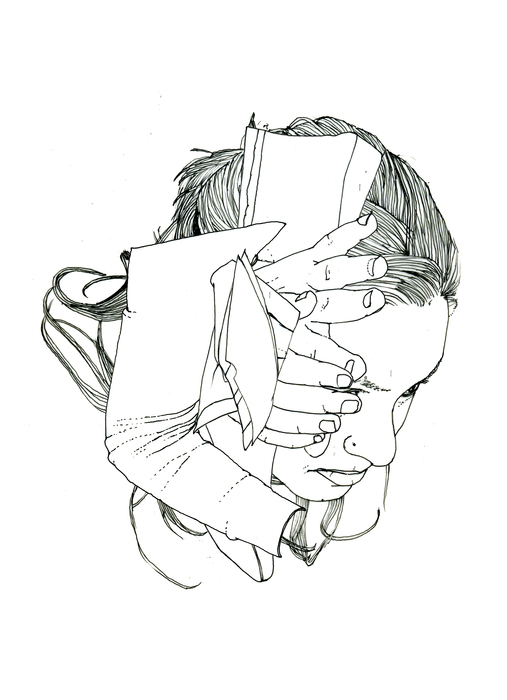

Images that I collected gradually entered my work, such as those related to 9-11. This process became a methodology that began with discussions about the images and their origins and led to photoshoots in my studio in Amsterdam where friends and myself posed, to reconstitute the image. These moments, of staging, led me to a deepened understanding of my relationship with the media. The photographs led to drawings which I eventually began to distort, fragment and collage. These manoeuvres allowed me a distance from which I could expand upon my own narratives.

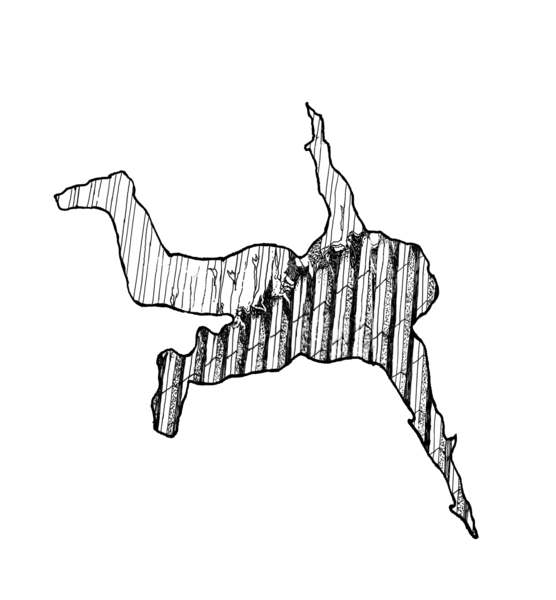

Of all the images of people leaping from the Towers to escape the inferno the lesser circulated was that of a woman falling, her arms outstretched arms with what looked like her skirt billowing out around her. I asked my partner, Irene, to pose in a manner that suggested by the image. After settling on the pose I went in close-up with the camera, mapping her. This lead to drawings of different sections of the body, which were then assembled together and re-constituted into the Falling Figure, which has become an image that repeats within my work.

The progressive Artists Group formed in 1947 by artists F.N. Souza, S.H. Raza, M.F. Hussain, K.H. Ara, H.A. Gade and S.K. Bakre with artists such as Tyeb Mehta, joining later, has influenced me in picturing the human body as a symbol of the time we live in. Tyeb Mehta's Falling Figures are propelled by the violence he saw engulf the country during the communal riots sparked by the Partition in1947

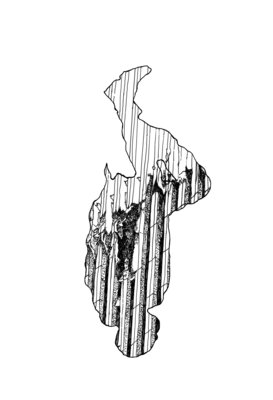

Having begun working with images related to unrest I became curious of exploring a similar narrative in my homeland. Kashmir, over which 3 wars have been fought between India and Pakistan since the subcontinent rid itself of colonial rule, had till then remained unfamiliar to me except via the media.

When Indian independence became imminent Britain, in 1947, decided to divide the subcontinent, laying down a border to form two countries, Pakistan and India and by doing so, dividing along communal lines a people that had historically been one. Kashmir, nestling between the soon to be carved borders of Pakistan and India with its population largely Muslim, was ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh (1896-1961), a Sikh King. When time came to choose between joining Pakistan, an Islamic democracy, or secular, democratic India, he dithered. This indecision set into play one of the most vexing of political problems within the country today.

I first visited Srinagar, the summer capital of Kashmir, in 2009, on a grant from a Museum Centro Cultural Montehermoso. While I was led to it to it by curiosity of its history, once there, I began looking beyond the media narrative, allowing my intuition to engage with this new environment. Walking through Srinagar gave me an initial understanding of its rich history and current state of decay. What had once been a beautiful city lay neglected, worn down by years of troubles.

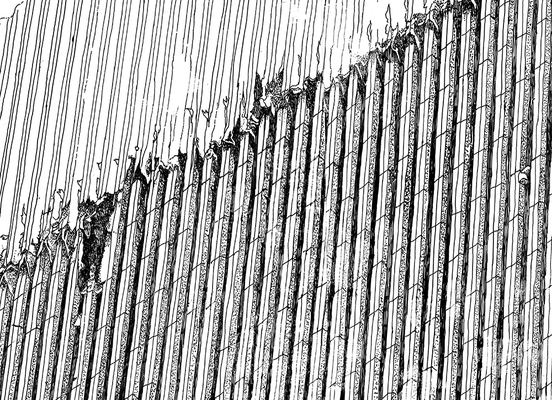

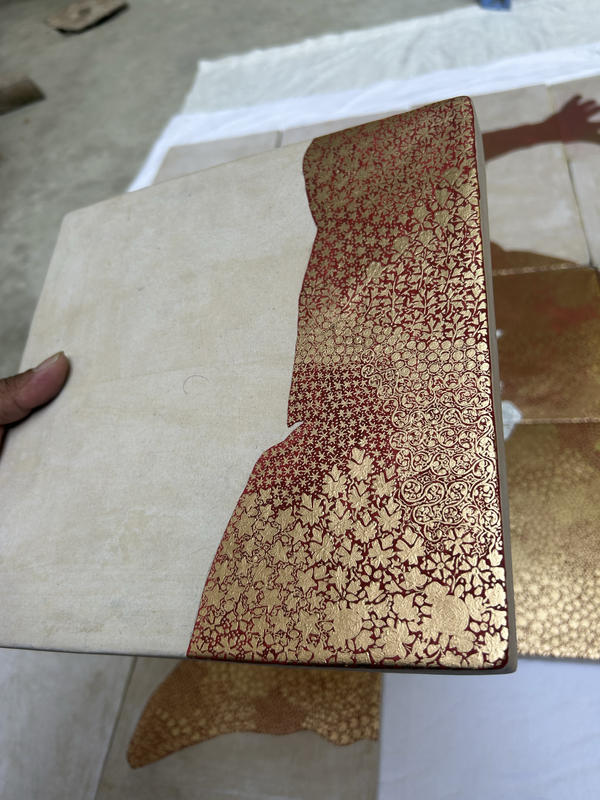

Amongst the many people I visited was the craftsman Fayaz Jan, located in the Shia community of Hasan Abad. I returned 5 years later in 2014 to work with him in creating an installation for Eva International, in Limerick, Ireland, curated by Bassam Al Baroni.Titled Srinagar (above, image credit Eamonn O' Mahoney). It was commissioned by Outset, UK and since then I have continued returning to Srinagar, working within this craftsman's community in Hasan Abad, digging gradually deeper into my narrative.

In Srinagar working with artisans, I found finally myself in an environment that I could perceive. Being an artist I share with them a language, that of image-making. And so I learned from them not only about the motifs they paint, but also their connection to the city. In fact these are entangled. The cities Sufi shrines, centuries old, are painted in motifs and colours that are repeated by them, painted by their hands upon paper-mache objects and dispersed within the craft market. Khanqah e Moula, built as a shrine to the Sufi preacher Mir Sayyid Ali Hamdani (1318-1384) is testament to this.

Papier-mâché, a popular craft, was introduced to Kashmir by sufi preachers from Central Asia and Iran, such as Mir Sayyid Ali Hamdani (1312-1385). They taught their believers craft techniques as a means for them to keep their hands busy and therefore closer to god. Thus, the craft of papier-mâché objects such as plates, caskets and animal shaped jewellery boxes decorated with finely painted motifs spread across Kashmir. While I had seen such objects since I was a child but never imagined they were made of papier-mâché.

I thought of translating this material into tiles, like a canvas, to paint on. It sounded reasonably simple a task, but took a long time, a year in fact, before we could have a surface that could be painted upon.

Once the tiles were prepared, I began working with the craftsmen in the Karkhana, or workshop, of the master craftsman Fayaz Jan in a tiny room in Hasan Abad. I decided to enter their working dynamic as an equal. I would share images with them, as well as understand the motifs they worked with. I learned their individual strengths and the motifs they excelled in. It is an embodied knowledge, a knowledge held in the hands and involved in making.

It is learned by looking, passed down over the generations, within family or through apprenticeship.

I was keen on building a platform that would allow us to share our knowledge. I found myself learning their motifs as well as absorbing their stories. I also tried to insert their way of working into my own imagery.

To me, the essence of materiality lies in translation. And translation can only happen when people feel the need to communicate. This is not always smooth, as conflicts occur. But they can be overcome, and to me the atmosphere activated when I work with the craftsmen is proof a world in which dialogue is possible.

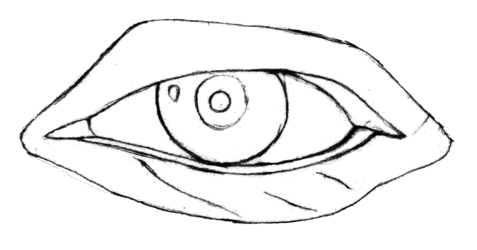

Interested in optical shifts and distortions I stumbled across the motif of St. Lucia online, in an altarpiece by Francesco del Costa (1473) which sits at the National Gallery of art at Washington DC. She holds in her hands a stem with two leaf like eyes. I learned that Lucia’s name originates from the Latin word for light, which is perceived by the eyes. I was intrigued by the fragmentation employed in making the eyes into a motif and thought to rework this motif using images of my own eyes as the leaves.

In You & Me two motifs are juxtaposed - the Falling Figure whose shapes filled in with red brushstroke over which the craftsmen have laid intricate motifs painted in gold. The second is the motif St Lucia. I added the Cosmos flower to the motif after seeing it bloom in Fayaz's garden. My wife, the artist Irene Kopelman, originally posed for the Falling Figure, which over the years has become a repeating trope within my work. The eyes in the flower are mine and so the work is also a portrait of the both of us!

Working with craftsmen, listening their stories rich in legends, suffused with proverbs, opened for me a window into their world and through them Srinagar, a city with 2000 years of lived history. Kashmir was an important centre for Buddhism — the 4th Buddhist Conference was held in Kashmir under the rule of Kanishka in 72 AD. Recently I learned a large stupa existed in the centre of the city, of which no sign remains. Miran Zain's tomb, a 14th century edifice, with its distinctive Central Asian architecture, is an anomaly in Srinagar. Adorning its brick facade is a glazed tile that could be read to be forged from an amalgamation of cultural and religious resources: Craftsmen draw from all that surrounds them. It is this accretion of culture, which is representative of a rich diversity of form that propels my narratives.